The recent meltdown in the British Gilt market that provided the rationale for the Bank of England to intervene in the markets by buying government bonds has raised the question now being asked rather uneasily by policy makers: could the same thing happen in the US ?

Of course it can. In fact it’s a virtual certainty unless steps are taken to reform both US fiscal policy, financial regulations and US financial infrastructure.

A dreary recitation of the numbers that describe the state of the public fisc has a tendency to fall on deaf ears, probably because various warnings have been issued for decades but disaster hasn’t arrived yet, or has been averted in the short term. But that is only on the surface. Putting off reform now just disguises the real cost of our fiscal folly and ultimately makes it more costly than it needs to be.

The truth is we have a structural deficit that will not be ameliorated by mere tactics. Under the current policy regime unsustainable growth in debt and deficits are baked into the cake for the foreseeable future. The deficit and accumulated debt will retard economic growth and make solving the problem more difficult.

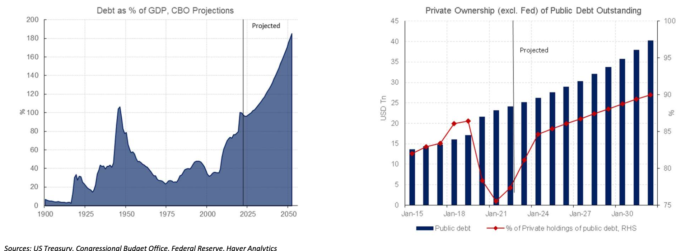

Consider the current state of affairs and projections for the future absent significant policy changes. According to the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC) accumulated Treasury debt has doubled since 2015 and, according to the CBO is projected to reach 180% of GDP by 2050. This will require increasing ownership of Treasury securities by the private sector reaching about 25% by 2030. (See the graphs below).

By definition that means that funds that would ordinarily go to the private sector, where they could fund investment, are going to the public sector where they mostly finance income transfer. These income transfer programs discourage savings and therefore investment needed to finance economic growth.

The biggest liabilities are in Social Security and Medicare. They contain unfunded promises to pay benefits of $60 and $100 trillion respectively, expressed in terms of present value. Those numbers, which dwarf accumulated Treasury debt of about $30 trillion, are off balance sheet. But off balance sheet or no, the Treasury needs cash to pay beneficiaries.

That’s one reason why the increasing fragility of financial markets is becoming problematic. With the rise in inflation to 40 year highs, the Fed has been aggressively raising interest rates. They have already raised overnight rates about 3 percentage points and before the end of the year those rates will probably be around another 1 % higher. Intermediate and longer rates have also risen about 3.5 percentage points in anticipation of additional Fed tightening.

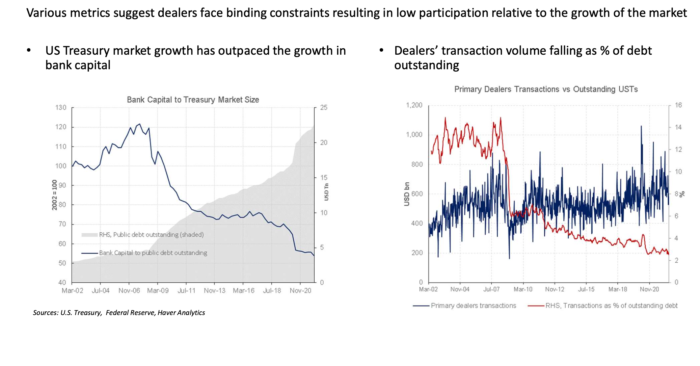

But while rates have risen along with Treasury financing requirements, bond dealers have pulled in their horns. According to the Treasury Advisory Borrowing Committee, bank capital has fallen sharply as a percentage of Treasury market size.

In November of 2008 during the cataclysmic events leading to the Great Recession, bank capital was about 22% of publicly held Treasury debt. Now it’s a shade under 5%. Similarly, over the same time period, primary dealer transactions in Treasuries fell from about 14% to 2% of outstanding Treasury securities. (See the accompanying graphs.)

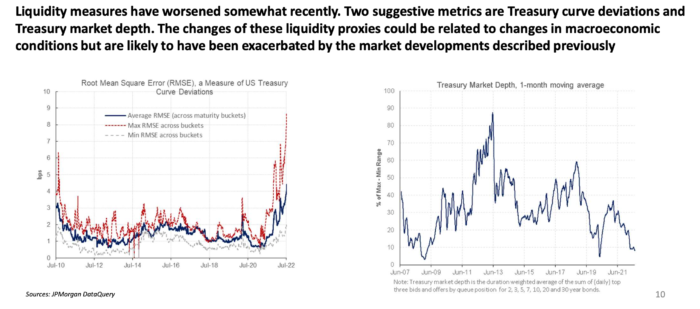

At the same time, there has been a substantial pick up in Treasury market volatility and diminished market liquidity. Data from JP Morgan, shown in the graphs below, illustrate a rapid rise in Treasury market volatility and corresponding fall off in market depth.

This is where the rubber meets the road. Theorists can argue all day long about what type of stress the market can handle. As a practical matter though, Treasury needs to sell securities to finance all the spending that Congress has ordered. And someone has to buy those very same securities. Standing between those buyers and sellers is the dealer community.

There are 25 primary dealers in government securities. Primary dealers are authorized to trade with the Fed. They also serve as market makers and make underwriting bids at Treasury auctions. According to data published by the Federal Reserve of New York, the top quintile of dealers—5 in total—account for about 50% of dealer transactions in Treasuries. The top 10—which includes the 1st and 2nd quintiles—account for about 75% of the volume.

The current weighted average maturity (WAM) of outstanding Treasury debt is about 74 months. The weighted average duration (WAD) of the debt is about 5 years. The CBO projects yearly deficits north of $1 trillion for years to come. If we take into consideration rolling over the existing debt along with financing deficits of $1 trillion plus for the foreseeable future, then we are talking about something in the neighborhood of $6 trillion worth of Treasury securities being sold through the dealer community every year for a very long time.

Remember there are only 25 dealers and 5 of them account for about half the trading volume. That means there will be about $500 billion worth of Treasuries every month being marketed by a very small number of players. And keep in mind that bank capital as a percentage of outstanding Treasury debt has been dropping like a stone. Also keep in mind that primary dealer transactions in Treasuries now constitute a mere 2% of outstanding Treasury debt, down from 14% a little over a decade ago. Combine that with a sharp rise in volatility and with shrinking market depth and we have the recipe for a financial calamity.

Could a meltdown like the one in Britain happen here? Sure it can. The elements that could touch it off are present. All it needs is a spark. The wise course would be to begin to reform our budgeting processes and strengthen our financial infrastructure before there is a spark. Which means that substantial policy reforms are due now, before it’s too late.

JFB